About this deal

Today, Shore is the director of photography at Bard College, where he started as a professor in 1982. He wears tortoiseshell glasses and a wardrobe of corduroy, wool, and tweed. His hair is gray and slightly wild. He appears so adapted to the professorial role that it’s a surprise to learn that he has almost no formal schooling of his own. In June 1972 the 24-year-old photographer and native New Yorker Stephen Shoreset off on a road trip, driving south, through Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas, into the deep South and Southwest.

Shore is recognised as being among the most influential post-war American photographers, and was included in the landmark exhibition New Topographics: Photography of a Man-Altered Landscape at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York in 1975 (alongside photographers including Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams and Bernd and Hilla Becher). His work is closely associated with conceptual practices as a result of his time at Andy Warhol’s Factory in the 1960s, and he is credited, along with William Eggleston (born 1939), with helping to establish colour photography as a valid medium. The fly-fishing comparison still holds, and his images, though no longer surprising, still evince intelligence, concentration, delicacy and attention. It’s the earliest work that intrigues the most, though, insofar as it shows the tentative emergence of a modern American master. As a teenager, Stephen Shore was interested in film alongside still photography, and in his final year of high school one of his short films, entitled Elevator, was shown at Jonas Mekas' Film-Makers' Cinematheque. There, Shore was introduced to Andy Warhol and took this as an opportunity to ask if he could take photographs at Warhol's studio, the Factory, on 42nd Street. Warhol's answer was vague and Shore was surprised to receive a call a month later, inviting him to photograph filming at a restaurant called L'Aventura. Shore took up this offer and, soon afterward, began to spend a substantial amount of time at the Factory, photographing Warhol and the many others who spent time there. He had, by this point, become disengaged with his high school classes and dropped out of Columbia Grammar in his senior year, allowing him to spend more time at the Factory. In American Surfaces, I was photographing almost every meal I ate, every person I met, every waiter or waitress who served me, every bed I slept in, every toilet I peed in. But also, I was photographing streets I was driving through, buildings I would see.”Content inseparable from attention to form. It occurs to me that there’s no such thing as a definitive Steven Shore photograph, except that it’s by default like nothing else. I recognize it, but not as an instance of “style.” It’s more like entry to a zone of immediate experience. I feel a little lost, as I do in my real life. You don’t pin down; you unpin up, if that makes any sense.

If this formalism looks forward to the more obsessive serialism of his American Surfaces, where he photographed the food he ate every day and the details of the bland motel rooms he stayed in, there are also street photographs that betray the influence of Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank. A dog in a window next to a huge Stars and Stripes is, at first glance, pure Frank – but there is something more seemingly casual about Shore’s eye. Shore was born in New York City in 1947, the sole son of Jewish parents who ran a handbag company. At the age of six, he began to develop his family’s photos with a dark-room kit his uncle had given him as a present. He received his first camera a couple years later, and when he was ten he received a copy of Walker Evans’ American Photographs. VH: You were born in New York City but your journey took you through small-town America. Were you looking to photograph communities that felt familiar to you or those that felt different from where and how you grew up?

Stephen Shore was born in 1947 and grew up on New York City's Upper East Side. Shore's family was Jewish, and he was the only child. The family owned a succesful business and Stephen lived a privileged existence, with annual trips to Europe and regular exposure to art and other forms of culture. He was given a darkroom set by an uncle when he was six, which he used to develop his family's snapshots, taken with a simple and inexpensive Kodak Brownie, often experimenting with different ways of printing the images using cardboard masks. Shore had little practice taking his own photographs, however, until the age of nine, when his parents bought him a 35 mm camera. Rene Ricard, Susan Bottomly, Eric Emerson, Mary Woronov, Andy Warhol, Ronnie Cutrone, Paul Morrissey, Pepper Davis For 22 months beginning in March 1972, Shore traveled across the continental United States with a simple Rollei 35 – a camera so diminutive in stature that it earned the title of smallest 35mm camera in production at the time [ more on the Rollei 35 can be seen here in our review]. It was this tiny camera which allowed him to blend in, to never give the air of a serious photographer, and which granted him accessibility to people and places without question or query. It was the normality, the civilian nature of a compact 35mm loaded with color film which let him make important work right under the noses of people looking for Leica-clad members of Magnum.

Together, they amounted to a new topography of the vernacular American landscape, his style in places approximating what came to be known as the snapshot aesthetic, in other places adhering to a detached, almost neutral formalism that only added to the deadpan everydayness of his images. Shore later described his democratic approach thus: “To see something ordinary, something you’d see every day, and recognise it as a photographic possibility – that’s what I’m interested in.” Though dismissed at the time by many critics, his style has been enduringly influential and he is now recognised as one of the greatest living photographers. Analog photography would seem to demand a more considered approach. If you’re shooting a plate of pancakes with an eight-by-ten, you’re forced to be conspicuous, highly intentional. Or is that wrong? Do you think your early photographs could have been shot digitally? Over the years, far more photographers have been drawn to the Uncommon Places pictures than any other made by Shore. This is, after all, the series which cemented his place as an early pioneer of color work in the critical art space. It is a large book filled with crisp images of immense detail. It is the kind of work every photographer vies to make in their lifetime. But American Surfaces is the book I revisit more than any other. It’s the book I wrote my college thesis about nearly a decade ago. To me, American Surfaces is a collection of images taken by a man living out his life. The more meditative Uncommon Places is too pre-occupied with composition to eat the damn pancake. I see much of your work, especially the digital work, as a sequence of enjoyments. You like the world. But, beneath that, there’s a serious sort of drive, which I don’t understand but am trying to. Your easygoing attitude doesn’t fool me, unless I’m a fool not to honor it.

Shore's images are structured around the experience of seeing, seeking to communicate the way in which the everyday might register to an outsider. He has regularly used his work as a form of visual diary, communicating his own experiences through his photographs. Shore's photographic choices suggest emotional states to the audience, often drawing power through the ways in which light and composition evoke feelings that the viewer cannot name.

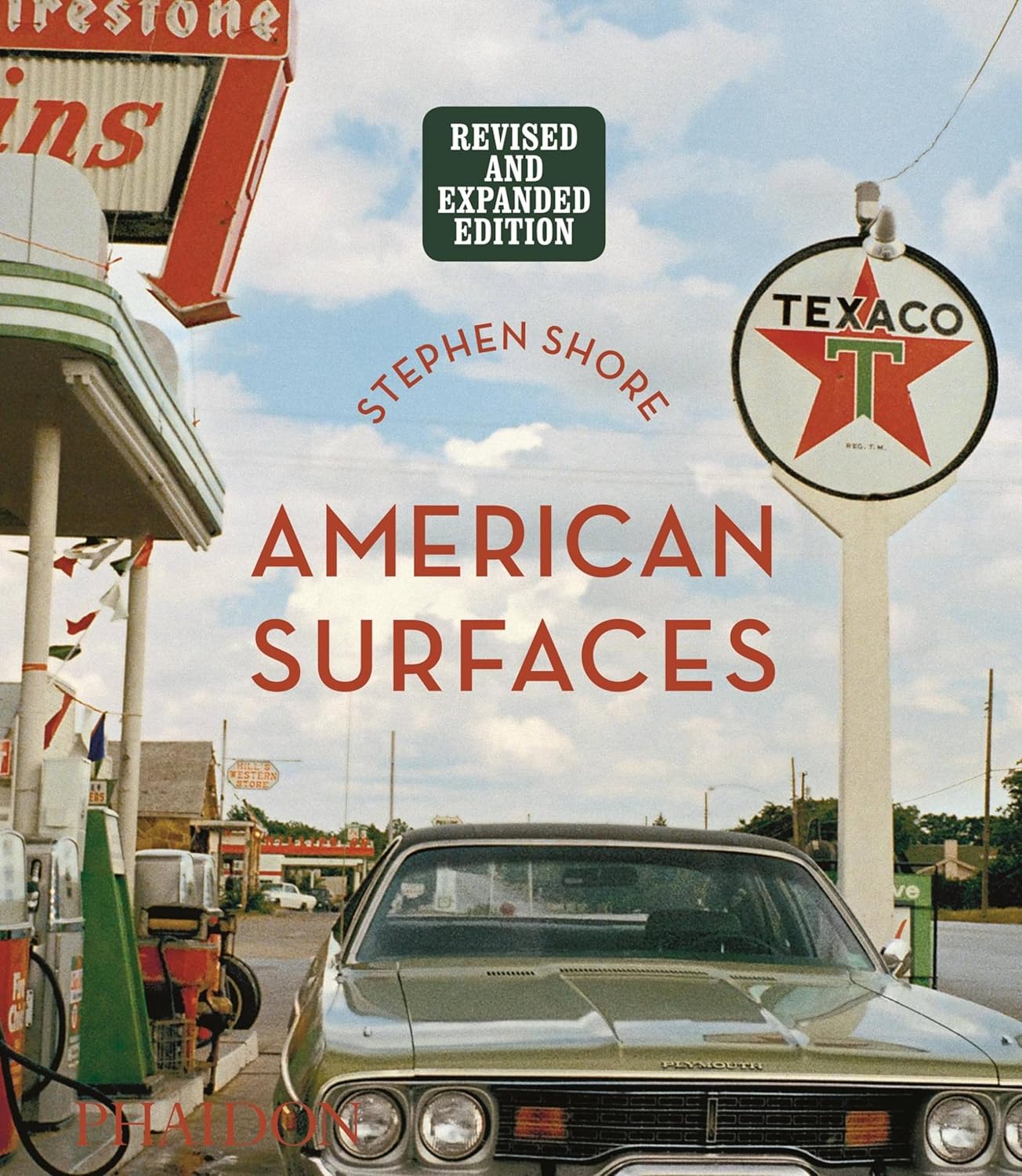

This image, from Shore's best-known series, Uncommon Places, shows a table set for breakfast at what appears to be a diner. The breakfast setting, on a table lined with a lamination imitating wood, is positioned on a diagonal from the camera. It consists of a plate of pancakes, encircled by Hopi petroglyphs, positioned between cutlery atop a placemat showing scenes of Native Americans and white colonizers. Further from the camera, occupying a central position at the top of the frame, is a smaller plate upon which sits a bowl holding half a cantaloupe. To the right are a salt shaker and a pepper shaker, a glass of water with ice and a glass of milk. In the lower left corner, the tan acrylic of the seat below is visible. He also has been working on a series about Holocaust survivors in Ukraine. It is an unusual project for Shore: Art critics have typically downplayed his photos’ content and discussed instead their formal qualities or conceptual ideas. “I’m self aware enough to know that when I’m doing this, I‘m photographing much more loaded subject matter than I’ve ever dealt with before,” Shore said. “So the question is: Can I take a picture that is not just an illustration of the content but is a visually coherent picture and that could stand alone even if one didn’t know what I was photographing and also somehow communicate some essence of the situation?” But the answer to your question could be different at another stage of development. For example, the work I did for “Steel Town,” in the fall of 1977, came at the end of the period of formal exploration I just described. By this time, I really had a handle on formal choices, and I could think about what to photograph and not about how. The content of the pictures was guided by the needs of the commission: to go to cities where mills were closing, and to photograph the mills, the cities, and the steelworkers. I had never dealt with such immediate economic conditions before. And this raised a larger, more central question, something you referred to in your recent review of the Constructivism show at MoMA: does art that springs from political situations have a “use by” date? I understood that a societal event could exist as history, as archetype, as metaphor—or, to use T. S. Eliot’s term, as an “objective correlative.” I hoped to find that point. American Surfaces was first published as a book of seventy-two images in 1999. In 2005, consistent with his practice of revisiting and reworking earlier series through the medium of the photobook, Shore published the series in its entirety for the first time, and applied a cohesive structure to the works, grouping them by year and the state in which they were taken (see Shore 2005). These digital prints owned by Tate were made in the same year in an edition of ten.This photograph of an intersection in Oklahoma is among the image sequence known as American Surfaces, taken on Shore's first drive across the United States. At the centre of the image is the point where two roads intersect, marked by a set of traffic lights and a vertical sign marking the Texaco station visible behind two cars on the right side of the image. The image has been taken late in the day and the lights are bright against the faded blue and orange sky, the dark green of the nature strips and the grey of the road and the foreground parking lot in which crumpled newspapers lie discarded. American Surfaces is intended to be seen as a sequence, in which the minor details of life on the road, including food on tables, beds and televisions in motels and gas stations such as this, build to communicate a sense of the North American interior as an anonymous monotony.

Related:

Great Deal

Great Deal